Main Page

Welcome to the Synthetic Cell Wiki (SynCellWiki). This wiki contains information about synthetic cells and is intended as a reference manual for engineers who are interested in using synthetic cells to engineer biology.

What is a Synthetic Cell?

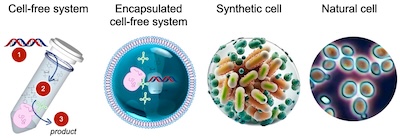

The term "synthetic cell" is not well-defined and different groups have used it in different ways over time. Other terms are also used: artificial cells, developer cells, and protocells are some examples. What all of these definitions have in common is the notion of some sort of contained and engineered biomolecular machine that carries out functions similar to that of a living cell. Some of the major categories of synthetic cells include:

- Encapsulated cell-free systems: A system consisting of a container of some sort, with biomolecular machinery inside the contained region that carries out biomolecular functions (transcription, translation, sensing, chemical processing, motility, etc). Synthetic cells in this class can range from very simple artificial vesicles containing a few proteins to complex biomolecular machines that carry out complex functions. As a general rule, synthetic cells in this category are not self-replicating, though they may include mechanisms for assembly into more complex consortia or multi-cellular machines.

- Biomimetic synthetic cells: A system that carries the key functions of a living cell, typically including compartmentalization, replication, and metabolism. These systems do not yet exist, but significant progress has been made on each of the basic functions, often using encapusulated cell-free systems as a starting point. A recent review and roadmap for this class of systems has been written by members of the US Build-A-Cell[2] consortium (Rosthschild et al, 2024[1]).

- Minimal cells: A natural cell that has been heavily modified to utilize a minimized chromosome while still supporting life. The prototypical minimal cell is JCVI-syn3.0[3], which consists of a modified Mycoplasma mycoides bacteria that has been modified to contain only 531,000 base pairs encoding 473 genes, making it the smallest genome of any self-replicating organism.

In this wiki, we will primarily focus on the technologies involved in the first two classes of synthetic cells, which are often referred to as "bottoms-up" synthetic cells, since they are built from non-living components.

How Could Synthetic Cells Be Useful?

This section summarizes some of the potential applications for synthetic cells. The Synthetic Cell Applications page has a more detailed analysis of current and future applications of synthetic cells.

Long Term Vision: Building Biological Machines at Scale

A long term goal for synthetic cells is to enable predictable engineering of complex "biomachines", where a biomachine is an engineered system that makes use of biomolecules to carry out a useful function. For example, imagine a world in which engineers can design and build a device that is 1-2 mm long, operates for 24 hours, and can be programmed to explore small spaces and retrieve objects and substances with well-defined chemical, mechanical, or optical properties. In nature, this is called a carpenter ant, and it consists of ~20M cells that allow the ant to explore its environment, find food or building materials for its nest, and communicate with other ants. The various cells in the ant carry out different functions (muscles, energy conversion, sensing, decision making, etc.) and are assembled together in a fashion that allows the system to operate autonomously, much like a self-driving car is able navigate on city streets. While engineers are able to build self-driving cars, we have not yet developed and mastered the engineering processes and workflows needed to engineer a system at the millimeter scale that can carry out similarly useful functions.

As a second example, imagine a biological machine that can extract chemicals and energy from the environment around it, transport the chemicals to processing centers where it combines and converts them into new molecules, and then transports them to packaging centers where its assembles them into a useful form. In nature, this is called an orange tree. The chemical engineering discipline can build machines that have these same high level functions (perhaps to produce chocolate oranges[4] [invented in 1932!]), but we don't know how to build a biological machine at this level of complexity and function. If we could, we might even be able to engineer it so that it made different types of fruits on different branche (apples, oranges, and plums?), or build different variants of the machine that were tuned to operate in different types of climate (from rainforests to semi-arid plains, depending on the model that you choose).

As a final example, and perhaps the most achievable in the near term, consider the idea of embedding synthetic cells into artificial and/or hybrid materials, similar to biofilms or perhaps slime molds. In this instantiation of synthetic, multicellular biomachines, the individual synthetic cells embedded in a material could sense conditions in their local environment and change the properties of the material in response to those conditions. For example, a material might adjust its mechanical or optical properties based on changes in temperature or chemical cues. Synthetic cells embedded in materials could also export chemicals to interact with the environment, perhaps degrading toxins or killing harmful organisms on the surface.

For all three of these cases (ants, plants, and slimes), synthetic cells are a possible starting point for many of the nanoscale and microscale functions that would need to be combined to produce these (multicellular) complex biomachines. Of course, there is no reason that these would need to mimic their natural counterparts completely. For example, rather than figuring out how to have cells grow, divide, and differentiate, we could instead assemble the cells using additive manufacturing techniques. And rather than building into each cell the ability to synthesize the energy it requires, we could simply feed energy into the system from an external source, much as we power a cell phone from a rechargeable battery or plug a computer into a wall outlet (via a power supply). Furthermore, we would not have to restrict ourselves to complete biological materials: it would be fine to 3D print some portions of the biomachine using conventional materials (e.g., plastics) and other parts using biomaterials (encapsulated as synthetic cells).

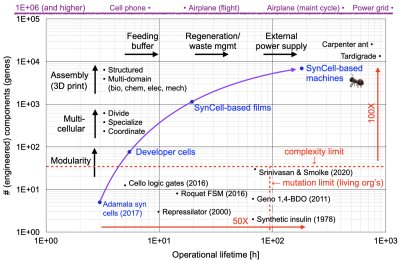

Why Are Synthetic Cells a Good Way to Get There?

One of the hypothesis of the synthetic cell movement is that building from the "bottom up" is more "engineerable" (predictable, robust, scaleable) than other approaches to building complex biomachines. The most obvious alternative is genetically modifying living organisms, and this is where the majority of work in synthetic biology currently takes place. But our record in engineering complex biological circuits and pathways in living organisms is not great: the most complex systems we have been able to to engineer to date have at most dozens of individually engineered components (see, for example, Srinivasan and Smolke, Science, 2020[5]), versus the millions of engineered components that are part of a cell phone, an airplane, or the power grid. One reason this might be the case is that when we engineer living systems, we are fighting against billions of years of evolution that have fine-tuned the organism we are engineering to carry out its specific function in nature, and we don't yet have the understanding or insight to modify that function in a way that is predictable, robust, and scaleable.

A major drawback of the synthetic cell approach versus more conventional approaches to engineering biology is that we have to re-invent all of the major subsystems from scratch. In particular, the need to "reinvent" metabolism is a major hurdle: natural cells come with the ability to metabolize carbon sources and turn them into energy and the other materials need for the cell to function. Synthetic cells must import the natural metabolic subsystem, reinvent metabolism, or find a different method for providing the power required to operate. The last approach seems to most plausible, but is an example of the significant challenges that must be overcome in order to make synthetic cells a viable alternative to genetically modified organisms.

More Achievable Starting Points (MVPs)

While building ants, plants, and slimes is perhaps a compelling long term vision, we are currently a long way from being able to achieve that. In the shorter term (2-10 years), here are a couple of examples of places synthetic cells might be useful on their own:

- Distributed Environmental Sensing, Recording, and Response: Collections of developer cells that monitor and record or respond to environmental conditions could be built for applications ranging from human health to agriculture to surveillance. For example, imagine a synthetic cell that displays proteins or other complexes on its surface that allow it to bind to target niches, then monitor the local chemical, mechanical, optical, or thermal environment in that niche. Upon detection of a selected combination of signals, the synthetic cell could record events in DNA (eg, using conditionally activated integrases to alter DNA in a predefined way) and the DNA could later be sequenced to recover the signal(s) seen by the synthetic cells. Alternatively, the synthetic cell could produce and/or release a chemical or protein into the external environment to locally respond to the environmental event.

- Adaptive Materials Systems: Building on some of the modules used for sensing, recording, and response, synthetic cells could be integrated with engineered materials to respond to environmental stimuli by modulating mechanical, chemical, or optical properties. For example, a collection of synthetic cells could be 3D printed to form a film with chemically- or thermally-reactive optical properties (e.g., changing reflectivity or color as a function of environmental cues, or tuning mechanical properties based on locally sensed events). The synthetic cells could be integrated with other materials (perhaps hydrogels or bioplastics) or with natural biofilms (for anti-fouling or biomanufacturing applications).

- Synthetic Cells as Replacements for EMERs. Engineered Microbes for Environmental Release (EMERs) are an emerging application area in synthetic biology with applications in agriculture, remediation, biomining, and therapeutics (animals or humans). EMERs can be challenging to use due to regulations governing the release of genetically modified organisms, in particular because they are often intended for open release, and so conventional containments strategies for genetically engineered organisms are not applicable. Replacing EMERs with (non-replicating) synthetic cells could provide a safer and more predictable method for carrying out existing biological functions such as nitrogen fixation, phenol degradation, or waste processing.

Current demonstrations of synthetic cells are primarily oriented at demonstrating basic capabilities.

What About Recreating Life?

As noted above, one of the motivations for many people in the synthetic cell field is to better understand the rules of life and maybe even to create new forms of life. While this is a valiant goal, in this book we take the point of view that while we want to make use of the various biological components that nature has provided, the engineering approach to implementing useful functions using those biological components might be different than what nature has done. So just as airplanes make use of the same lift and draft mechanisms as birds but implement flight in very different ways, synthetic cells might make use of the same core mechanisms as biology (transcription, translation, enzymatic processing, etc) but not do so in a way that we would consider to be "living".

Synthetic Cell Subsystems

We return now to the individual synthetic cell, and what is required to implement such a device as a building block for more complex biomachines.

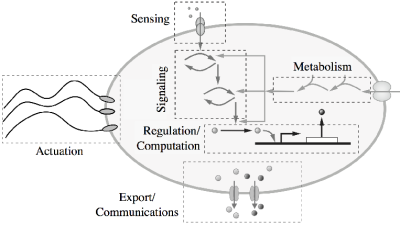

We break of up our description of synthetic cells into a set of "subsystems" that are responsible for the primary molecular mechanisms of the cell. Each of these mechanisms is described in more detail on the linked page.

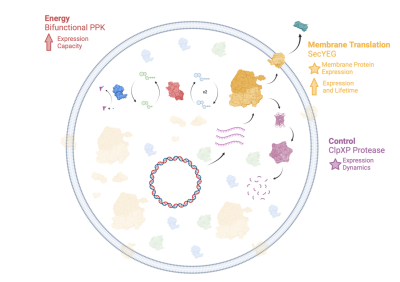

- Cytoplasm: The Cytoplasm Subsystem is responsible for implementing and maintaining the internal environment of the synthetic cell, including key mechanisms such as transcription, translation, and degradation.

- Container: The Container Subsystem is responsible for encapsulating the components of the synthetic cell, as well as supporting transfer of information and materials from the inside of the cell through the appropriate sensing and transport subsystems.

- Sensing, Transport, and Communications: The Sensing Subsystem is responsible for allowing the cell to obtain information about the external and internal environment. Sensed signals can include chemical concentrations, temperature, forces, light, or other biological, chemical, or physical entities. The Transport Subsystem is responsible for transporting materials across the synthetic cell boundary (membrane), either passively or actively, and will different levels of specificity. The Communications Subsystem is used to send information from one synthetic cell to another.

- Regulation and Logic: The Regulation Subsystem maintains the internal environment of the cell and is responsible for providing robustness in the presence of uncertainty as well as allowing the design of the dynamics of the cell. The Logic Subsystem is responsible for implementing internal logic that can control the operations of the synthetic cell. In its simplest form, it carries out logical operations such as AND and OR functions, but more complex logic including finite state machines can also be used if needed.

- Metabolism: The Metabolic Subsystem provides the energy required for the cell to operate. It can either consist of a mechanism for directly transferring energy from an external source or it can convert energy from one form into another.

- Motility and Adhesion: The Motility Subsystem is responsible for generating forces in a what that allows a synthetic cell to move in its environment. The Adhesion Subsystem is used to attach a synthetic cell to other synthetic cells or other objects in the environment.

Which of these systems is present depends on the applications needs of the synthetic cell. We note that in the synthetic cells described here, we do not include a replication subsystem, since we are focused on non-replicating synthetic cells.

Modeling and Specifications

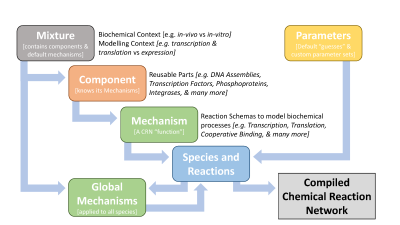

Throughout this wiki, Python-based simulation models will be used to illustrate the dynamic characteristics of the subsystems and to build computational representations of interconnected subsystems. We will make use of the BioCRNpyler package[7], a software framework and library designed to aid in the rapid construction of models from common motifs, such as molecular components, biochemical mechanisms and parameter sets. These parts can be reused and recombined to rapidly generate chemical reaction network (CRN) models in diverse chemical contexts at varying levels of model complexity.

BioCRNpyler compiles high-level specifications into detailed CRN models saved as SBML. Specifications may include: biomolecular components, modeling assumptions (mechanisms), biochemical context (mixtures), and parameters. BioCRNpyler is written in Python with a flexible object-oriented design, extensive documentation, and detailed examples to allow for easy model construction by modelers as well as customization and extension by developers. BioCRNpyler make use of the following abstractions (see the BioCRNpyler[7] documentation for more details):

- Species and Reactions make up a CRN and are the output of BioCRNpyler compilation. Many sub-classes exist, such as ComplexSpecies and reactions with different kinds of rate function (e.g. mass-action, Hill functions, etc).

- Mechanisms are reaction schemas, which can be thought of as abstract functions that produce CRN Species and Reactions. They represent a particular molecular process, such as transcription or translation. During compilation, Mechanisms are called by Components. Global Mechanisms are called at the end of compilation in order to affect all species of a given type or with given attributes — for example, dilution of all protein Species.

- Components are reusable parts; they know what kinds of Mechanisms affect them but are agnostic to the underlying schema. For example, a promoter is a Component which will call a transcription Mechanism; similarly, a Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) is a Component which will call a translation Mechanism. However, the same Promoter and RBS can use many different transcription and translation Mechanisms depending on the modeling context and detail desired.

- Mixtures are sets of default Mechanisms and Components that represent different molecular and modeling contexts. As an example of molecular context, a cell-extract model requires reactions to consume a finite supply of fuel, while a steady-state model of living cells does not have a limited fuel supply. As an example of modeling context, a simple model of gene expression may have a gene catalytically create a protein product, while a more complex model might include cellular machinery such as RNA polymerase and ribosomes with Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

- Parameters are designed for flexibility; they can default to biophysically plausible values (such as a default binding rate), be shared between Components and Mechanisms, or have specific values for Component-Mechanism combinations. This system is designed so that models can be produced quickly without full knowledge of all parameters and then refined with detailed parameter files later.

The Nucleus Developer Cell Platform

Nucleus[8] is an open source platform for synthetic cell builders maintained by b.next—an SF-based startup company focused on rebuilding biology for engineering—that provides standardized protocols, design tools, component libraries, and reference designs for the full process of cell building. The platform encompasses comprehensive resources for cytosol construction, DNA content engineering, and membrane encapsulation, offering researchers a complete toolkit for developing functional synthetic cells. Currently in its fifth stable release (v0.3.0), Nucleus represents a systematic approach to making synthetic biology more accessible and standardized.

The Nucleus platform supports the development of various specialized synthetic cell types, including detector cells, emitter cells, and responder cells, enabling researchers to create cellular systems capable of molecular sensing and response. By providing both the integration architecture and practical materials needed for synthetic cell construction, Nucleus bridges the gap between conceptual design and actual implementation in synthetic biology research. The platform emphasizes open science principles with all materials freely shareable, fostering collaboration and transparency within the synthetic biology community. This open-source approach allows researchers worldwide to contribute to and benefit from the collective advancement of synthetic cell technology.

The Nucleus platform uses the OpenMTA[9] material transfer agreement, developed as a collaborative effort led by the BioBricks Foundation and OpenPlant, which allows open sharing of DNA with attribution (similar to an open source software license). Nucleus also uses the CERN Open Hardware License - Permission [10] for distribution of modules and protocols. Documentation of Nucleus modules are done via Developer Notes[11], an open access, short form mechanism for scientific communication.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 L. J. Rothschild, N. J. H. Averesch, E. A. Strychalski, F. Moser, J. I. Glass, R. Cruz Perez, I. O. Yekinni, B. Rothschild-Mancinelli, G. A. Roberts Kingman, F. Wu, J. Waeterschoot, I. A. Ioannou, M. C. Jewett, A. P. Liu, V. Noireaux, C. Sorenson, and K. P. Adamala, Building synthetic cells─From the technology infrastructure to cellular entities. ACS Synthetic Biology 13(4):974-997, 2024. DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.3c00724

- ↑ https://buildacell.org. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025.

- ↑ C. A. Hutchison III, R.-Y. Chuang, V. N. Noskov, N. Assad-Garcia, T. J. Deerinck, M. H. Ellisman, J. Gill, K. Kannan, B. J. Karas, L. Ma, J. F. Pelletier, Z.-Q. Qi, R. A. Richter, E. A. Strychalski, L. Sun, Y. Suzuki, B. Tsvetanova, K. S. Wise, H. O. Smith, J. I. Glass, C. Merryman, D. G. Gibson, and J. C. Venter, Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 351:aad6253, 2016. DOI:10.1126/science.aad6253

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terry%27s_Chocolate_Orange. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025.

- ↑ P. Srinivasan and C. D. Smolke. "Biosynthesis of medicinal tropane alkaloids in yeast". Nature 585(7826):614–19, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2650-9.

- ↑ D. Del Veccho and R. M. Murray, Biomolecular Feedback Systems. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 https://biocrnpyler.readthedocs.org. Retrieved 13 Sep 2025

- ↑ https://nucleus.bnext.bio. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025.

- ↑ https://www.openplant.org/openmta. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025.

- ↑ https://gitlab.com/ohwr/project/cernohl/-/wikis/uploads/3eff4154d05e7a0459f3ddbf0674cae4/cern_ohl_p_v2.txt. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025

- ↑ https://devnotes.bnext.bio. Retrieved 19 Jul 2025