Synthetic cell demonstrations: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

This page provides an overview of synthetic cell demonstrations reported in the scientific literature. The information was generated using a prompt requesting examples of synthetic cell demonstrations from specific research groups, processed by Claude Sonnet 4 on August 29, 2025. The examples focus on bottom-up approaches to creating artificial cellular systems with life-like behaviors. | |||

== Vesicle-based Demonstrations == | |||

== | === Light-Activated Communication in Synthetic Tissues (2016) === | ||

[[File:Placeholder-booth-2016.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing light-activated synthetic tissue]] | |||

Booth and colleagues developed one of the earliest demonstrations of sophisticated synthetic cell communication using light-activated control systems.<ref name="Booth2016">Booth, M. J., Schild, V. R., Graham, A. D., Olof, S. N., & Bayley, H. (2016). Light-activated communication in synthetic tissues. Science Advances, 2(4), e1600056.</ref> The system involved 3D-printing droplets containing PURE cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems that could produce α-hemolysin pore proteins upon light activation. When these pore proteins were incorporated into specific bilayer interfaces, they mediated rapid, directional electrical communication between subsets of artificial cells, mimicking neural transmission in living tissue. The light activation provided precise spatial and temporal control over which cells could communicate, creating the first demonstration of tissue-like organization in synthetic cell systems. | |||

=== | === Engineering Genetic Circuit Interactions Within and Between Synthetic Minimal Cells (2017) === | ||

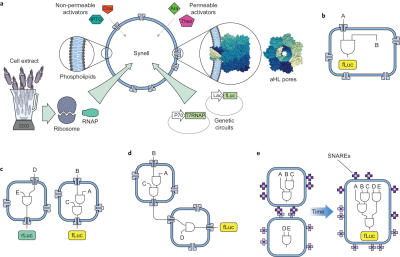

[[Image:adamala_syncell.png|400px|thumb|alt={Adamala et al., 2017 Figure 1}| | [[Image:adamala_syncell.png|400px|thumb|alt={Adamala et al., 2017 Figure 1}| | ||

Overview of genetic circuit interactions within and between synthetic cells. Adamala et al, 2017, Figure 1.<ref name="Adamala2017"/>]] | Overview of genetic circuit interactions within and between synthetic cells. Adamala et al, 2017, Figure 1.<ref name="Adamala2017"/>]] | ||

Adamala and Boyden demonstrated the first robust example of genetic circuit-based communication between populations of synthetic cells.<ref name="Adamala2017">Adamala, K. P., Martin-Alarcon, D. A., Guthrie-Honea, K. R., & Boyden, E. S. (2017). Engineering genetic circuit interactions within and between synthetic minimal cells. Nature Chemistry, 9(5), 431-439.</ref> Their system used liposome-encapsulated genetic circuits that they termed "synells" (synthetic minimal cells). The most sophisticated demonstration involved two distinct populations: sensor synells containing IPTG and genetic circuits to produce α-hemolysin, and reporter synells containing circuits that responded to released signaling molecules (doxycycline and IPTG) by expressing firefly luciferase. The α-hemolysin created pores in membranes, allowing controlled release of signaling molecules and establishing cascaded communication between the two cell populations without crosstalk. | |||

=== | === DNA-Based Communication in Populations of Synthetic Protocells (2019) === | ||

[[File:Placeholder-joesaar-2019.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing DNA communication between protocells]] | |||

Joesaar, Mann, de Greef and colleagues developed a highly sophisticated platform called "biomolecular implementation of protocellular communication" (BIO-PC) using proteinosomes as artificial cell chassis.<ref name="Joesaar2019">Joesaar, A., Yang, S., Bögels, B., van der Linden, A., Pieters, P., Kumar, B. V. V. S. P., ... & de Greef, T. F. A. (2019). DNA-based communication in populations of synthetic protocells. Nature Nanotechnology, 14(4), 369-378.</ref> The system leveraged enzyme-free DNA strand-displacement circuits encapsulated within semipermeable protein-polymer microcapsules. The most complex demonstration showed bidirectional communication and distributed computational operations, where protocells could sense DNA-based input messages, process them through programmable logic circuits, and secrete output DNA strands that activated neighboring protocells. The encapsulation protected the DNA circuits from nuclease degradation, allowing operation in concentrated serum conditions. | |||

=== Controlling Secretion in Artificial Cells with a Membrane AND Gate (2019) === | |||

[[File:Placeholder-kamat-2019.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing mechanosensitive artificial cell]] | |||

= | Kamat's group at Northwestern developed artificial cells capable of mechanosensitive secretion using membrane-based AND gate logic.<ref name="Kamat2019">Hilburger, C. E., Jacobs, M. L., Lewis, K. R., Peruzzi, J. A., & Kamat, N. P. (2019). Controlling secretion in artificial cells with a membrane AND gate. ACS Synthetic Biology, 8(6), 1224-1230.</ref> The system used giant unilamellar vesicles containing mechanosensitive channels (MscL) that required both membrane tension and specific chemical signals to open. When both conditions were met, the channels allowed controlled release of encapsulated cargo molecules. This represented one of the first demonstrations of Boolean logic operations implemented through membrane biophysics in synthetic cells, providing a foundation for developing smart therapeutic delivery systems that could respond to multiple environmental cues. | ||

=== TXTL-Based Synthetic Cell Systems (2021) === | |||

[[File:Placeholder-noireaux-2021.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing TXTL synthetic cells]] | |||

Noireaux's group developed the all-E. coli TXTL toolbox 3.0 for creating synthetic cell prototypes using cell-free transcription-translation systems.<ref name="Noireaux2021">Garenne, D., Thompson, S., Brisson, A., Khakimzhan, A., & Noireaux, V. (2021). The all-E. coli TXTL toolbox 3.0: new capabilities of a cell-free synthetic biology platform. Synthetic Biology, 6(1), ysab017.</ref> The most sophisticated demonstration involved semi-continuous synthetic cells where liposomes loaded with TXTL reactions could produce enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) at concentrations exceeding 8 mg/ml. This was achieved by allowing chemical building blocks to diffuse through membrane channels, creating a feeding mechanism that sustained protein synthesis over extended periods. The system also demonstrated the synthesis of complex biological entities, including the complete bacteriophage T7 (40 kb genome, ~60 genes) at concentrations of 10^13 PFU/ml. | |||

== Other Compartmentalization Techniques == | == Other Compartmentalization Techniques == | ||

=== Biomimetic Behaviours in Hydrogel Artificial Cells through Embedded Organelles (2023) === | |||

[[File:Placeholder-elani-2023.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing hydrogel artificial cells with organelles]] | |||

Elani's group at Imperial College developed a microfluidic strategy to create biocompatible cell-sized hydrogel-based artificial cells with embedded functional subcompartments acting as synthetic organelles.<ref name="Elani2023">Allen, M. E., Hindley, J. W., O'Toole, N., Cooke, H., Contini, C., Law, R. V., ... & Elani, Y. (2023). Biomimetic behaviours in hydrogel artificial cells through embedded organelles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(26), e2221863120.</ref> The most advanced demonstration showed cells capable of stimulus-induced motility, where embedded catalase organelles decomposed hydrogen peroxide to generate oxygen bubbles, propelling the artificial cells through solution. The cells could also perform content release through activation of membrane-associated proteins and establish enzymatic communication with surrounding compartments through cascaded chemical reactions. This represented the first demonstration of complex, multi-modal cellular behaviors in hydrogel-based synthetic cell systems. | |||

=== | === Minimal Cell Division Systems Using Protein Oscillations === | ||

[[File:Placeholder-schwille-mindce.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing MinCDE protein oscillations]] | |||

Schwille's group at the Max Planck Institute reconstituted the bacterial MinCDE protein oscillation system that directs cell division in E. coli.<ref name="Schwille2021">Loose, M., Fischer-Friedrich, E., Ries, J., Kruse, K., & Schwille, P. (2008). Spatial regulators for bacterial cell division self-organize into surface waves in vitro. Science, 320(5877), 789-792.</ref> The most sophisticated demonstration showed that just two proteins (MinD and MinE) plus ATP could create self-organized protein waves on artificial membrane surfaces that sensed membrane geometry in both two and three dimensions. These waves replicated the natural oscillatory behavior that positions the division plane in bacterial cells. When confined in artificial compartments, the system could recognize shape, geometry, and size, providing the foundation for developing self-dividing artificial cell compartments. | |||

=== | === Artificial Platelets Using Mechanosensitive Channels === | ||

[[File:Placeholder-liu-platelets.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing artificial platelet system]] | |||

Liu's group at the University of Michigan developed artificial platelets that couple mechanical forces to enzymatic activities using the mechanosensitive channel MscL.<ref name="Liu2019">Liu, A. P., et al. (2017). The living interface between synthetic biology and biomaterial design. Nature Materials, 21(4), 390-397.</ref> The system used lipid vesicles containing reconstituted MscL channels that opened in response to membrane tension, allowing transit of small molecules and triggering cascaded enzymatic reactions. When mechanical forces were applied to the artificial platelets, the channels activated and released stored chemical factors, mimicking the force-sensitive activation of natural platelets. This work provided a framework for developing mechanosensitive synthetic cells for therapeutic applications and established principles for coupling physical stimuli to biochemical responses in artificial cellular systems. | |||

=== | === Self-Assembling Membrane Systems with Metabolic Cycles === | ||

[[File:Placeholder-devaraj-metabolism.jpg|thumb|300px|Placeholder for image showing self-assembling membrane metabolism]] | |||

Devaraj's group at UCSD developed artificial cells capable of abiotic phospholipid metabolism that generates and maintains dynamic membrane systems.<ref name="Devaraj2025">Fracassi, A., Seoane, A., Brea, R. J., Lee, H. G., Harjung, A., & Devaraj, N. K. (2025). Abiotic lipid metabolism enables membrane plasticity in artificial cells. Nature Chemistry.</ref> The most advanced system demonstrated a metabolic network that could synthesize phospholipids de novo from simple precursors, enabling artificial membranes to grow, remodel their composition, and maintain themselves away from equilibrium. The system used chemoselective coupling reactions to "stitch together" lipid fragments in situ, creating self-reproducing lipid compartments that could undergo cycles of growth and division. This work represented the first demonstration of synthetic metabolism that could sustain dynamic membrane systems without biological enzymes. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 17:23, 29 August 2025

This page provides an overview of synthetic cell demonstrations reported in the scientific literature. The information was generated using a prompt requesting examples of synthetic cell demonstrations from specific research groups, processed by Claude Sonnet 4 on August 29, 2025. The examples focus on bottom-up approaches to creating artificial cellular systems with life-like behaviors.

Vesicle-based Demonstrations

Light-Activated Communication in Synthetic Tissues (2016)

Booth and colleagues developed one of the earliest demonstrations of sophisticated synthetic cell communication using light-activated control systems.[1] The system involved 3D-printing droplets containing PURE cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems that could produce α-hemolysin pore proteins upon light activation. When these pore proteins were incorporated into specific bilayer interfaces, they mediated rapid, directional electrical communication between subsets of artificial cells, mimicking neural transmission in living tissue. The light activation provided precise spatial and temporal control over which cells could communicate, creating the first demonstration of tissue-like organization in synthetic cell systems.

Engineering Genetic Circuit Interactions Within and Between Synthetic Minimal Cells (2017)

Adamala and Boyden demonstrated the first robust example of genetic circuit-based communication between populations of synthetic cells.[2] Their system used liposome-encapsulated genetic circuits that they termed "synells" (synthetic minimal cells). The most sophisticated demonstration involved two distinct populations: sensor synells containing IPTG and genetic circuits to produce α-hemolysin, and reporter synells containing circuits that responded to released signaling molecules (doxycycline and IPTG) by expressing firefly luciferase. The α-hemolysin created pores in membranes, allowing controlled release of signaling molecules and establishing cascaded communication between the two cell populations without crosstalk.

DNA-Based Communication in Populations of Synthetic Protocells (2019)

Joesaar, Mann, de Greef and colleagues developed a highly sophisticated platform called "biomolecular implementation of protocellular communication" (BIO-PC) using proteinosomes as artificial cell chassis.[3] The system leveraged enzyme-free DNA strand-displacement circuits encapsulated within semipermeable protein-polymer microcapsules. The most complex demonstration showed bidirectional communication and distributed computational operations, where protocells could sense DNA-based input messages, process them through programmable logic circuits, and secrete output DNA strands that activated neighboring protocells. The encapsulation protected the DNA circuits from nuclease degradation, allowing operation in concentrated serum conditions.

Controlling Secretion in Artificial Cells with a Membrane AND Gate (2019)

Kamat's group at Northwestern developed artificial cells capable of mechanosensitive secretion using membrane-based AND gate logic.[4] The system used giant unilamellar vesicles containing mechanosensitive channels (MscL) that required both membrane tension and specific chemical signals to open. When both conditions were met, the channels allowed controlled release of encapsulated cargo molecules. This represented one of the first demonstrations of Boolean logic operations implemented through membrane biophysics in synthetic cells, providing a foundation for developing smart therapeutic delivery systems that could respond to multiple environmental cues.

TXTL-Based Synthetic Cell Systems (2021)

Noireaux's group developed the all-E. coli TXTL toolbox 3.0 for creating synthetic cell prototypes using cell-free transcription-translation systems.[5] The most sophisticated demonstration involved semi-continuous synthetic cells where liposomes loaded with TXTL reactions could produce enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) at concentrations exceeding 8 mg/ml. This was achieved by allowing chemical building blocks to diffuse through membrane channels, creating a feeding mechanism that sustained protein synthesis over extended periods. The system also demonstrated the synthesis of complex biological entities, including the complete bacteriophage T7 (40 kb genome, ~60 genes) at concentrations of 10^13 PFU/ml.

Other Compartmentalization Techniques

Biomimetic Behaviours in Hydrogel Artificial Cells through Embedded Organelles (2023)

Elani's group at Imperial College developed a microfluidic strategy to create biocompatible cell-sized hydrogel-based artificial cells with embedded functional subcompartments acting as synthetic organelles.[6] The most advanced demonstration showed cells capable of stimulus-induced motility, where embedded catalase organelles decomposed hydrogen peroxide to generate oxygen bubbles, propelling the artificial cells through solution. The cells could also perform content release through activation of membrane-associated proteins and establish enzymatic communication with surrounding compartments through cascaded chemical reactions. This represented the first demonstration of complex, multi-modal cellular behaviors in hydrogel-based synthetic cell systems.

Minimal Cell Division Systems Using Protein Oscillations

Schwille's group at the Max Planck Institute reconstituted the bacterial MinCDE protein oscillation system that directs cell division in E. coli.[7] The most sophisticated demonstration showed that just two proteins (MinD and MinE) plus ATP could create self-organized protein waves on artificial membrane surfaces that sensed membrane geometry in both two and three dimensions. These waves replicated the natural oscillatory behavior that positions the division plane in bacterial cells. When confined in artificial compartments, the system could recognize shape, geometry, and size, providing the foundation for developing self-dividing artificial cell compartments.

Artificial Platelets Using Mechanosensitive Channels

Liu's group at the University of Michigan developed artificial platelets that couple mechanical forces to enzymatic activities using the mechanosensitive channel MscL.[8] The system used lipid vesicles containing reconstituted MscL channels that opened in response to membrane tension, allowing transit of small molecules and triggering cascaded enzymatic reactions. When mechanical forces were applied to the artificial platelets, the channels activated and released stored chemical factors, mimicking the force-sensitive activation of natural platelets. This work provided a framework for developing mechanosensitive synthetic cells for therapeutic applications and established principles for coupling physical stimuli to biochemical responses in artificial cellular systems.

Self-Assembling Membrane Systems with Metabolic Cycles

Devaraj's group at UCSD developed artificial cells capable of abiotic phospholipid metabolism that generates and maintains dynamic membrane systems.[9] The most advanced system demonstrated a metabolic network that could synthesize phospholipids de novo from simple precursors, enabling artificial membranes to grow, remodel their composition, and maintain themselves away from equilibrium. The system used chemoselective coupling reactions to "stitch together" lipid fragments in situ, creating self-reproducing lipid compartments that could undergo cycles of growth and division. This work represented the first demonstration of synthetic metabolism that could sustain dynamic membrane systems without biological enzymes.

References

- ↑ Booth, M. J., Schild, V. R., Graham, A. D., Olof, S. N., & Bayley, H. (2016). Light-activated communication in synthetic tissues. Science Advances, 2(4), e1600056.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Adamala, K. P., Martin-Alarcon, D. A., Guthrie-Honea, K. R., & Boyden, E. S. (2017). Engineering genetic circuit interactions within and between synthetic minimal cells. Nature Chemistry, 9(5), 431-439.

- ↑ Joesaar, A., Yang, S., Bögels, B., van der Linden, A., Pieters, P., Kumar, B. V. V. S. P., ... & de Greef, T. F. A. (2019). DNA-based communication in populations of synthetic protocells. Nature Nanotechnology, 14(4), 369-378.

- ↑ Hilburger, C. E., Jacobs, M. L., Lewis, K. R., Peruzzi, J. A., & Kamat, N. P. (2019). Controlling secretion in artificial cells with a membrane AND gate. ACS Synthetic Biology, 8(6), 1224-1230.

- ↑ Garenne, D., Thompson, S., Brisson, A., Khakimzhan, A., & Noireaux, V. (2021). The all-E. coli TXTL toolbox 3.0: new capabilities of a cell-free synthetic biology platform. Synthetic Biology, 6(1), ysab017.

- ↑ Allen, M. E., Hindley, J. W., O'Toole, N., Cooke, H., Contini, C., Law, R. V., ... & Elani, Y. (2023). Biomimetic behaviours in hydrogel artificial cells through embedded organelles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(26), e2221863120.

- ↑ Loose, M., Fischer-Friedrich, E., Ries, J., Kruse, K., & Schwille, P. (2008). Spatial regulators for bacterial cell division self-organize into surface waves in vitro. Science, 320(5877), 789-792.

- ↑ Liu, A. P., et al. (2017). The living interface between synthetic biology and biomaterial design. Nature Materials, 21(4), 390-397.

- ↑ Fracassi, A., Seoane, A., Brea, R. J., Lee, H. G., Harjung, A., & Devaraj, N. K. (2025). Abiotic lipid metabolism enables membrane plasticity in artificial cells. Nature Chemistry.